Back on the bikes - leaving Argentina

After three full months of being off the bikes sightseeing in Patagonia, Antarctica and northern Argentina and Chile, it was time to get back in our saddles and ride north to Bolivia. With the bag of goodies Kacia’s parents had brought us, we replaced worn bike tires and tubes, adjusted brakes, and changed the oil in our Rohloff hubs.

We gathered the necessary documents to apply for Bolivian visas. We printed out a dozen pages each of personal documents (photocopies of passports, yellow fever vaccinations, travel itinerary, bank statements, first night hotel reservation), purchased US$320 in crisp, newly minted U.S. bills from a money changer standing on the corner of Salta’s main plaza, grabbed our passports and visa photos, and went to the Bolivian consulate… twice. They didn’t have U.S. visa stickers, so we embarked on the 5-day ride to the border without visas. Note that U.S. citizens have the distinction of having to meet Bolivia’s most stringent visa requirements.

Since we’d spent so much time in the high desert with Kacia’s parents, we opted to enter Bolivia to the northeast of Salta, in the low tropical forest lands. Riding from Salta we passed through large scale agriculture lands – first tobacco farms, then sugar cane. When possible, we followed rural roads, but most of the ride was on a 2-lane highway with no shoulder, requiring us to bail out onto the dirt shoulder regularly to make way for passing trucks.

The level of affluence dropped precipitously, and the number of dead dogs on the road increased disturbingly. Our last night in Argentina was in a hotel without potable water (our first such experience in all of Argentina), in a town with mud streets, where we dined on a hot dog (a.k.a. a "Superpancho") and hamburger from a street vendor because the town’s only restaurant had been permanently closed because “people can’t afford to pay what we need to charge.”

Along the way to the Bolivian border we were treated to several nice surprises. Arriving in the town of Libertador General San Martin, we were enthusiastically greeted by two members of the developing tourism office, and thanks to their Facebook post, the local TV station showed up at our hotel later that night for a friendly interview. There we enjoyed a visit to the neighboring Calilegua National Park, a large protected area of the Yungas region's subtropical forest, containing the largest portion of Argentina’s biodiversity.

The next day, at a gas station picnic table, we were serendipitously reunited with Slav, a Bulgarian bike tourer who, with his partner Yana, had stayed as Warmshowers guests in our home in San Mateo, California, in 2016 as they biked through the U.S. Slav is a talented baker, and we munched on delicious rolls he had baked over a campfire the night before as we swapped stories, before continuing along our paths in opposite directions.

On our last day in Argentina, we received a gift from a “road angel”… a woman from the previous night’s hotel discovered that we had left our Camelbaks behind (our source of drinking water as we ride), and she hopped on a motor scooter and tracked us down, about 3 km later, to deliver them to us!

Entering Bolivia

After a lengthy process at the international border requiring all the paperwork we brought, we succeeded in getting 90-day Bolivian visas. We pedaled across the river that divides the countries into the bustling town of Bermejo, Bolivia.

Bolivia is a country with a vast diversity of landscapes and climates, from dry altiplano to tropical rainforest. It has a large indigenous population of several ethnicities and languages, and officially became the “Plurinational State of Bolivia” in 2009 under current President Evo Morales, who is the country's first indigenous president (of the Aymara community). Since its independence from Spain in 1825, Bolivia has lost half of its territory to its neighbors, Peru, Chile, Brazil and Paraguay. The most devastating was the loss to Chile of its territory on the Pacific coast, which landlocked Bolivia. The country is rich in natural resources, especially minerals, but it lacks processing facilities (and apparently the will to create them) and therefore exports most of its raw materials to Chile and other nations, who profit greatly from turning these commodities into products.

We had been warned by Argentinians, and even by fellow bike tourers, not to expect a warm welcome in Bolivia. Our experience was just the opposite. Bolivians were at least as curious about our recumbent bikes as other South Americans, and they were second only to the Colombians in their outgoing welcome of us. Our cost of living in Bolivia became the lowest we’d experienced in South America, but the standard of living for the locals was actually higher than we’d expected. The majority of tourists we met in Bolivia were Bolivians, from various cities throughout the country. Almost all of the rest of the tourists were French.

Bolivia has a thriving make-do, entrepreneurial culture. In Bermejo when we sought to buy SIM cards for our phones to enable us to make calls and use the internet, we were directed by the locals to a tiny convenience store that seemed to carry the inventory of an entire department store. In all the other South American countries to date, getting our cell phones on the local network had been amazingly easy. We had just popped in a new SIM card, added some money to the new phone number’s account, and dialed a number to activate a prepaid usage plan. In Bolivia, the state-owned network required registration with a name and state ID number. As foreigners, we were unable to register. Undaunted, the store owner pulled out of her pocket the crumpled ID of some local young man unknown to us and registered both our cell phone accounts in his name. We were up and running!

We quickly discovered Salteñas, delicious Bolivian empanadas served in the mornings, and were joyously reacquainted with cheap, fresh squeezed fruit juices that we had become accustomed to before spending time in Chile and Argentina. In Bolivia, we were delighted to learn, dinnertime starts at 5 or 6 pm (compared to 8:30 pm in Argentina).

When we first rolled into Bermejo, Clark’s Achilles tendon mysteriously and very painfully flared up. A convenience store sold us ice in the form of a frozen, refilled 2-liter plastic soda bottle. We stayed a couple of days in Bermejo to rest and ice the tendon, refreezing the 2-liter bottle every night in the hotel’s refrigerator.

Tarija - high altitude wine country

When Clark's tendon didn’t improve, we decided to keep moving, and hopped a bus from the humid tropical forest of Bermejo to the Mediterranean climate of Tarija in the heart of Bolivia’s wine region, where Clark could keep resting his achilles while we sampled the local products. Contrary to our expectations of another nerve-wracking South American bus ride, the trip was very tranquilo, thanks to a mellow and responsible driver.

Tarija was a comfortable city to spend some time in. We explored it with Luís, who runs the city’s free walking tour.

There were gentle, stray dogs everywhere, nearly all wearing sweaters as a result of a half-hearted attempt by locals to care for them. We stumbled on a clever park for kids to educate them about traffic laws and safety. We walked to the town’s kitschy wine glass mirador, attended a Bolivian ethnic dance exhibition in the main theater, ate peanut soup for lunch in the central market, and snacked on cheese pastries and api (thick, hot, sweet purple corn drink) in the afternoon at a streetside stall.

We took a “trufi” (the mainstay of Bolivian public transportation – a minivan with a designated route that will stop anywhere en route for passengers, and will expertly secure to its roof any cargo, from heavy sacks of potatoes to mattresses to new office furniture) to the lovely neighboring town of San Lorenzo to visit the home of Eustaquio “Moto” Mendez, a Bolivian revolutionary hero.

Tarija’s wines grow at over 1,800 m (6,000 ft), making it one of the world’s highest wine regions. Our full-day wine tour included a historic winery with a speed tasting of sweet wines distinguishable only by color, in which a dozen wine glasses filled to the brim were passed from hand to hand around a semi-circle of tasters, each sipping from the same glass as it passed. Fortunately, the tour also visited several vineyards with tasty dry wines that we would later look for in restaurants and stores. Our favorite was Campos de Solano’s Único Tannat.

Inca trail trekking

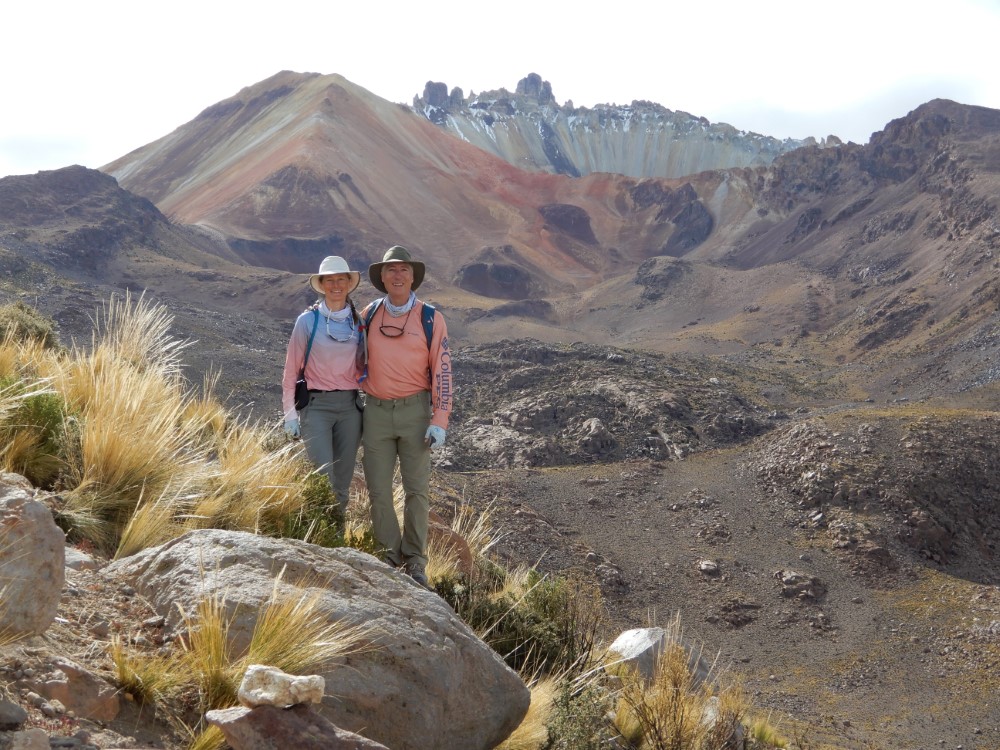

With Clark’s tendon feeling better, we embarked an unguided 3-day backpacking trip near Tarija. We took a bus to the altiplano at 3790 m (12,400 ft), got off at a remote intersection in the road, and entered the Cordillera de Sama Biological Reserve. The first day was flat, past a salty lake with flamingoes, surrounded by hills covered in golden grass clumps and some distant sand dunes. We camped in a dry wash that offered some protection from the wind, and filtered water from a silty lake. The next morning we happened upon a deep, clear pool of spring water we wish we'd found the night before and filled up.

We climbed past a few, tiny adobe villages and wandering llama herds. At the top of a pass we came to an intact section of Inca Trail, on which we walked for more than 20km as it descended back down to Tarija’s elevation. The second night we camped behind a stone wall, and Clark walked a km across a dry river bed to the opposite side of the valley to find a trickle of spring water. Again, we were close to a spring-fed pool that we didn't find until the the next morning.

We rejoined the Inca trail in a river gorge, followed it up to another pass and then down again. The trail was a treasure -- still in great condition, paved with large flat stones, and engineered by the Incas with switchbacks to maintain a gentle grade that enabled swift communication, distant trade, and transport of the Inca royalty.

The hike, including the aggressive descent, did not aggravate Clark’s tendon at all. Assuming it was healed, we loaded up the bikes and rode away from Tarija, and were stopped by a radio reporter for a quick interview along the way. But within the first 4 km it became clear that the tendon was not ready to ride. Walking and hiking was fine; pedaling was not. So we doubled back and went straight to the bus station to catch a ride to our next destination, Tupiza. The daily buses had already left, so we spent one more night in Tarija and took a bus the next morning, saving us five days of riding over several passes. Once again, the driver was mellow and the ride was smooth.

Tupiza

In Tupiza, we found the town celebrating its anniversary with a parade of workers (labor unions, merchants, and municipal employees) accompanied by school marching bands. The streets were closed and filled with people playing foosball, kids on trampolines and in bouncy-houses, and snack food vendors cooking skewers of meat and whipping up cotton candy.

We realized then that we had seen parades with marching bands, whether celebrating or protesting, in both Bermejo and Tarija, too. It turns out that Bolivians love parties, and marching bands, dancing, and fireworks are very common.

To give Clark’s tendon more time to rest, we joined a friendly French couple on a 4-day jeep tour from Tupiza to Uyuni, traveling long distances along rough, sandy dirt roads through Bolivia’s southern altiplano desert. Although this region is where most bike tourers ride across Bolivia, we had no desire to ride it. We had heard bikers’ stories of pushing their bikes through kilometers of sand, weighed down by multiple days’ worth of water and food, and being too cold at night in their tents. We sent our fully loaded bikes on the train from Tupiza to Uyuni, and they were waiting for us at the Uyuni station when we arrived by jeep 4 days later. It was cheap, easy, and worked perfectly.

Jeep trip through Bolivia's southern lake district

Anselmo, our jeep driver and guide, proved also to be a decent mechanic when an engine hose busted within the first hour of the first day. The jeep tour took us along the Bolivian side of the border with Chile, very near where we had previously traveled with Kacia’s parents. The terrain was therefore familiar, but the sights were unique and the trip worthwhile.

We visited eroded sandstone and towering mudstone rock formations, green and red desert lakes with flamingos and other waterfowl, hot springs, geysers, a deep river gorge, and a ghost mining town.

Anselmo ensured our trip’s safety by opening his door to drop coca leaves as an offering to Pachamama (Mother Earth)at the top of every pass. He proudly prepared us a cocktail in the colors of the Bolivian flag (red for blood spilled in wars, yellow for the country’s mineral wealth, and green for its fertile land). Julia, our well-educated, feminist cook and assistant guide, quickly prepared hot meals in the hostels, where we spent frigid nights warmly tucked under a mountain of heavy wool blankets.

The third night’s hostel, on the edge of Bolivia’s giant salt flat, Salar de Uyuni, was constructed of salt bricks and the floor was crushed rock salt.

Before dawn, we drove across the dry, flat, salt surface of the Salar, seeing in the distance the lights of a facility mining lithium from the Salar. We watched the sunrise from Isla Incahausi, one of several islands in the salt flat. It’s a mound of volcanic rock formed under an ancient giant lake, now covered in fossilized algae and tall, thriving cactus.

The jeep trip ended in Uyuni, at the town’s strangely compelling “train cemetery.”

Uyuni

In Uyuni, we visited the Casa de Ciclistas and made daily short bike rides to test Clark’s tendon. The tendon wasn't 100% yet, but was feeling better, so we decided to start traveling by bike again.

We loaded up and pedaled back to the Salar to have the unique experience of riding on the vast plain of salt. The dry season made this possible. The salt surface of the lake was hard, cracked and bumpy. We saw through some holes in the salt that the water table was immediately below the surface. The dry season is in the winter, so it was cold at night (-10˚C) at 12,000 ft elevation. We camped on the salt, away from the main vehicle track, and were treated to an hour-long 360-degree sunset, and a silent, windless, starry night.

Salar de Uyuni

We lunched at Isla Incahuasi at a salt picnic table, and were welcomed by Alfredo, the island’s hardy resident caretaker since 1982, who maintains a guestbook of bike tourers from all over the world.

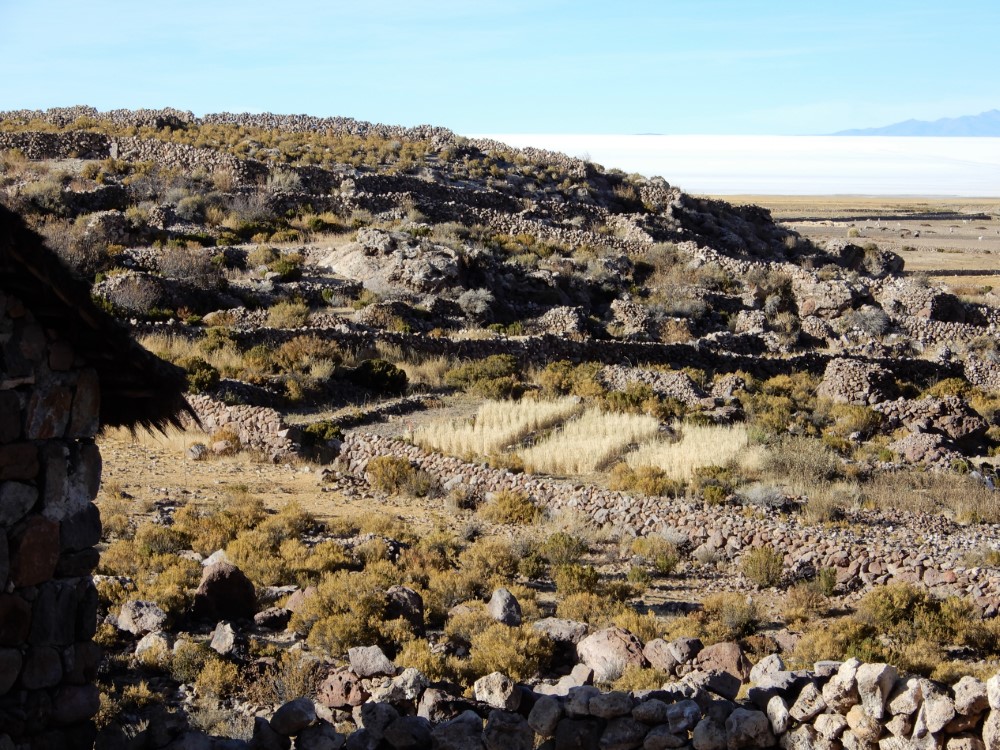

We then turned north and crossed the Salar to the flanks of Volcán Tunupa, where the salty soil is apparently perfect for quinoa farming. Surrounding a few small but active communities, the hillside was covered in abandoned adobe homes and fallow fields enclosed by stone walls — signs of what must have been a large population that once thrived on the shores of the Salar.

Coqueza and Volcán Tunupa

We arrived in Coqueza, a village of 25 families, as they were preparing for their town’s annual celebration of their patron saint, San Antonio de Padua. At the hostel, young men in the marching band were repainting their drum heads with white shoe polish, and the family was decorating their car with brightly colored blankets, plastic flowers, and stuffed teddy bears and taxidermy armadillos for a very short parade. The only restaurant was closed for the festivities, so the hostel let us cook in their kitchen. The 3-day progressive party moved from house to house, led by the village’s marching band and followed by dancing townspeople and buckets of spiked punch. Altars were built around the plaza, and the church was opened for its once-a-year mass delivered by a visiting priest.

We hiked to Coqueza’s two natural treasures: a cave containing seven well-preserved mummies still in their original location, and the stunningly colorful crater of Volcán Tunupa with views across the Salar. This town was a highlight or our travels through Bolivia.

Pedaling the altiplano

We continued cycling around the volcano, along the shore of the Salar, occasionally pushing our bikes through sandy sections of the dirt road, to the town of Salinas de Garci Mendoza with its striking blue church. We then pedaled three more days across the windy high altiplano, past dry, salty lake beds, quinoa farms, and a couple of large, round volcanic crater-like depressions.

We camped both nights – the second night for lack of lodging where we expected it. That night we filled our Tupperware with a hot chicken stew from a street vendor, filled our water bags, and pitched our tent on a sandy soccer field. A loud, thunderous sandstorm kicked up suddenly, filling our tent and covering our sleeping bags with sand. We dove into the tent just before the rain started, and gratefully ate our hot meal as the storm briefly, but powerfully, pounded outside.

Our next destination, the high silver mining city of Potosí, would have been a 4-day climb by bike, or a 4-hour ride by bus. We decided to take a bus to avoid pushing Clark’s Achilles too hard. Serendipitously, when we arrived at the crossroads town of Challapata, we spotted a bus picking up passengers on its way to Potosí. Within minutes we had removed our panniers and seats, folded the bikes, and loaded them into the belly of the bus. With another mellow driver at the wheel, we were on our way to our next adventure in this fabulously diverse country of Bolivia!

We are currently in Uruguay with friends from Portland. To find out where we are at any given moment, check our Track My Tour page, where we post a photo and blurb every day that we’re on the move. Also, you can get more up-to-the-minute, spontaneous updates if you follow Clark's accounts on Instagram and/or Facebook.