We arrived in Perú by overnight bus from Ecuador on September first, crossing the border at 2 am. The bus route took us from high in the Andes all the way down to Perú’s Pacific coast, which is pure sandy desert for the entire 2500 km length of the country.

Perú’s dry desert coast

Our first impressions were of endless sand, sand covering every outdoor surface, heaps of trash along the road and blown across the sandy terrain, and visible poverty well beyond what we’d observed in either Colombia or Ecuador. However, the monotone tan color of the coast is interrupted periodically by green pockets of civilization and agriculture, nourished only by runoff from the snowy Andes, not by local rainfall. As a result, ancient cultures that once thrived here (and their buried treasures) remained well-preserved. Surprising to us, half of Perú’s entire population of 32 million people still chooses to live in this harsh desert environment.

Chiclayo and the pre-Columbian Moche culture

The northern town of Chiclayo, where our bus ride ended and our bike ride began, was in one of these agricultural pockets in the desert, surrounded by industrial-scale rice paddies and mills. Chiclayo is a vibrant middle-class city with excellent food, including the local specialty of cilantro rice with duck (“arroz con pato.”) Less remarkable was the sweet “King Kong” dessert – a ridiculous stack of shortbread cookies layered with dried fruit paste and “manjar,” a sweet milk-based creamy spread. We were also introduced to the best coffee of the trip: Perú’s “café pasado”, in which you add concentrated liquid coffee (“coffee essence”) and sugar (each to your own taste) to either hot water or hot milk.

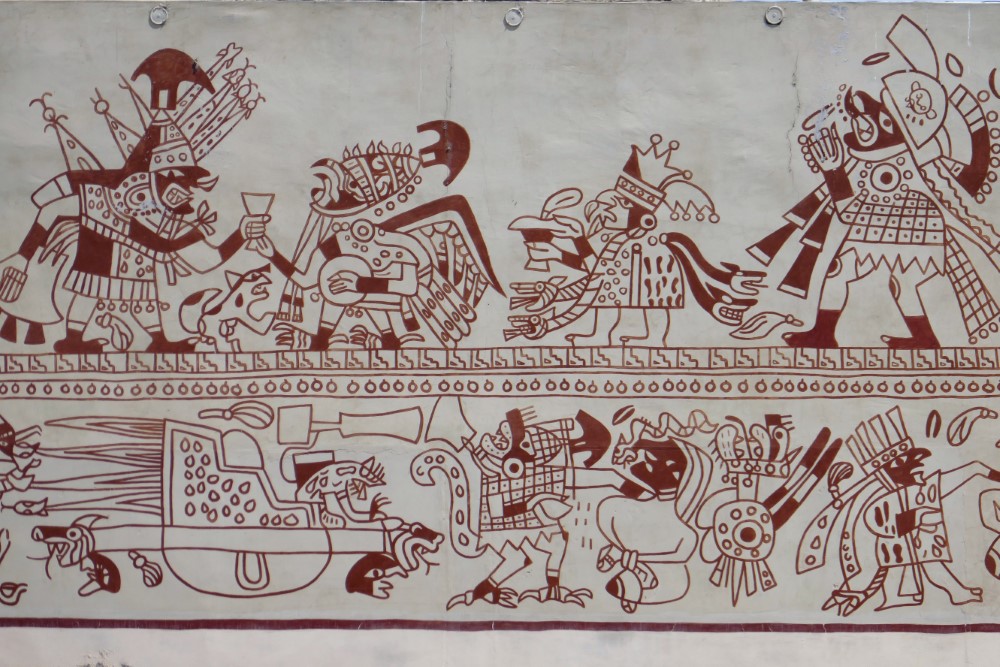

The real attractions here are the excavated ruins of the Moche culture (50-700 AD) and the Museum of the Royal Tombs of Sipán in in the neighboring town of Lambayeque. We toured the museum on the first Sunday of the month, which is a nationwide day of free museum access for Peruvians, so the museum was packed and abuzz with excited kids and families. The ancient tombs were layered deep inside adobe pyramids that had eroded to look like ordinary hills, and were only rediscovered in 1987. The museum houses the opulent artifacts, now meticulously restored, that were buried with two generations of Moche kings and clerics. Interestingly, the visitor is exposed to the artifacts in the layers in which they were unearthed -- spiraling through the museum from the top down. To our eyes, the quality and condition of the artifacts arguably rivals that of the tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh, King Tut. Unfortunately, no photos were allowed in the museum, but you can get a glimpse of the grandeur here. The artifacts shown in our photos here are from the nearby older (and lesser) Brüning museum.

Cycling in Perú

We came to Perú for the mountains, so when we started cycling, we quickly left the coastal Panamerican Highway and turned inland to higher elevations. Very few rural families here have cars, so most people either walk or ride a motorcycle, or pay for a ride in one of the ever-present three-wheeled mototaxis, a beat-up white 1990s-era Toyota Corolla station wagon taxi (there are millions of these) or in the back of an open-bed truck. Peruvian drivers are aggressive and recklessly fast, and there are way too many memorials on the sides of the roads for lives lost in accidents. However, the presence of pedestrians, livestock, mototaxis, and frequent speed bumps in the road raises drivers’ expectation of slow-moving vehicles and obstacles, improving our comfort and safety. Also, drivers here are constantly honking to warn other vehicles of their presence, so we have ample warning as a vehicle approaches.

Cajamarca’s arts scene

After crossing our first pass at 3,230 m, we coasted down past a large mountain-top quarry kicking up so much dust that it filled the air across the whole valley below. Our destination was Cajamarca, a historic city at the top of the valley. We were escorted into the city center by a passing motorcyclist that volunteered to show us the way. The main Plaza de Armas was adorned with gardens and surrounded by beautiful colonial buildings.

The plaza was bustling with an artistic exhibition. At night, dozens of artists with easels and paint palettes were positioned around the plaza using headlamps or cell phone flashlights to illuminate the dark scenes they were capturing on their canvases, and a new crop of painters was out there again the next morning to portray daytime scenes. There was a non-stop series of live music in the plaza ranging from a police marching band to a Mexican-style mariachi band, with some folk dancing thrown in. On an adjacent pedestrian way, wood and stone chips were flying for two straight days as sculptors raced to complete their works of art in the allotted time. We were even treated to live music during meals, since here, like in Colombia and Ecuador, restaurants will mute their stereo when a busking musician asks to enter and perform.

High above Cajamarca, we visited Cumbemayo, a hilltop of naturally-formed rock towers from which the local people in 1500 BC carved an impressive 9-km long aqueduct through solid basalt to divert precious water across the continental divide and back to Cajamarca. Petroglyphs along the canal give archeologists clues as to its construction and use.

Chachapoyas and pre-Inca ruins

In order to see some important archeological sites in northeastern Perú, we left our bikes on the roof of the guesthouse in Cajamarca and hopped a 12-hour bus northeast to the town of Chachapoyas, named for a pre-Inca culture that lived in the hills along a deep, broad limestone river canyon full of caves, and now full of archeological treasures. The bus ride itself was memorable, as it traversed a one-lane road on a cliff-hanging 2000 m descent. And whom should we encounter on that road when the bus stopped for lunch at a roadside restaurant? Our Australian friends, Tracey and Stephano, heroically pedaling their bikes in the opposite direction. When the bus then overheated on its next ascent, our driver hailed an oncoming truck driver, who willingly shared some coolant to get us back underway.

From Chachapoyas we took guided day trips to several sites. First was a hike to Gocta Falls, an impressive cascade, even in the dry season, that freefalls 771 m (2350 ft) in two sections over a vertical limestone cliff. It wasn’t mapped until 2006, and now its disputed ranking among the world’s tallest waterfalls ranges between 3rd and 16th, depending on the source.

Next we ascended to the mountaintop ruins of Kuélap via a newly constructed aerial tram — part of the government’s recent and urgent efforts to protect and promote these sites for tourism. Kuelap was a city of 3,500 or so inhabitants built atop a mountain that was leveled by a high retaining wall around the perimeter, through which there are only three narrow entrances. The area was filled edge-to-edge with round stone houses, each of which had a stone porch outside and a guinea pig pen inside (a food source). There is also a round temple that may have been a solar observatory. The round architecture was unlike any we had seen to date.

Third, we walked to the Revash adobe mausoleums built under an overhang on a high cliff to house the offerings and prepared remains of the Chachapoyas elite. The hills in this area are apparently filled with similar mausoleums and sarcophagi. The museum in Leymebamba has an extraordinary exhibit of the bundled remains from these pre-Inca mausoleums and sarcophagi, plus dozens of well-preserved mummies found in local caves from the Inca culture that ultimately ruled here. The Chachapoyas area is hard to reach, but worth the effort.

Rural riding south of Cajamarca

After a 12-hour overnight bus back to Cajamarca that wiped us out in the same way a 15-hour overseas flight does, we were reunited with our bikes and soon started riding south. We had been 9 days off of the bikes, so we planned mellow riding days, and they were delightful. One day we stopped for a mid-day soak in thermal waters. The roads were rural and quiet, with occasional clusters of small adobe houses, and increasingly grand vistas. In one rural area, nearly every family manufactured Spanish roof tiles from clay harvested in their yard and then fired in a round adobe kiln next to their house, using the eucalyptus trees they farm nearby for fuel.

The small villages on these rural roads have no restaurants for lunch, so we carry food for picnics. We buy the fruits and veggies available from local vendors (mandarin orange, banana, pepino, carrot, cucumber, tomato, and, if we’re lucky, avocado) and local bread rolls and honey. We are careful to carry small change, since the locals never have more than a few Soles to make change.

We haven’t needed to camp, as the towns we’ve stopped in have had at least one simple guesthouse. Most rural guesthouses have been rustic - one with a dirt floor, one with the outdoor toilet flushed with water from a bucket, one with no water between 7 pm and 6 am (it’s common for municipal water to run only part of the day, but usually a guesthouse will have a rooftop storage tank — this one didn’t), and of course no internet. We often find restaurants in these towns closed, so we’ve eaten more meals from market stalls and street vendors. As a result, we eventually both got sick, as have all travelers we’ve met in Perú, as sanitation and water quality standards are lower in Perú than in Colombia and Ecuador.

When we do find a restaurant open, menu options are limited to one or two choices being served that day — usually rice, french fries and fried meat. Now we sadly avoid the small salad that often accompanies the meal. At dinner we also try to order tomorrow’s breakfast to improve our chances that the restaurant will open in the morning. Breakfast is either fried eggs on rice, fried eggs in bread, or our new favorite pre-ride fuel -- chicken noodle soup with potatoes and a hard boiled egg. There is no refrigeration in most stores or restaurants. Milk is rarely available, so we frequently drink coffee black, but have also enjoyed the local warm sweet oatmeal, quinoa or bean porridge drunk from a mug in the mornings.

Perú’s recently paved mountain roads are a delight, climbing at a comfortable grades with nice flat switchbacks. It's gotten us to really think about, and appreciate, what goes into a good mountain road. We’ve also ridden quite a few km on dirt roads - some by choice as scenic shortcuts, and others by surprise when the “main” road suddenly became unpaved for days. The dirt is hard work and significantly slows our progress, frequently requiring pushing through water hazards or around steep switchbacks, but the traffic has been incredibly light and the scenery unbeatable.

Huamachuco’s famous plaza

The sizable colonial town of Huamachuco is known for its huge, beautiful plaza filled with topiary, and beloved by the locals. The town also has a notable festival in which a 40 m tall pole is hand carried in a long parade to the plaza, where it is erected with a huge red and white flag to launch the annual celebration of the town's patron saint. We missed the festival, but we saw similar flagpoles in numerous nearby small villages. We stayed in Huamachuco a day to visit Marcahuamachuco, the pre-Inca ruins of a vast walled city atop a craggy hilltop.

Cachicadán’s hot springs

After a confidence-building dirt road shortcut that passed the first of many open pit mines, followed by a long, winding, narrow descent on unexpected pavement, we arrived in the small town of Cachicadán to a festival in the main square. The student band was playing to a plaza full of of people to celebrate the public school’s anniversary -- a common practice, as we later found out in other towns. The town enjoys thermal waters, and our guesthouse had 6 thermal baths available for rent - free to us as guests. The baths were constantly full, as the thermal water doesn’t reach people living lower in town, so they walk up the hill and pay 3 soles ($1) for a bath. Our guesthouse had access ONLY to thermal water, so we walked further uphill to a public faucet to get cold water to filter for our drinking water.

In Cachicadán, we were invited to attend a political campaign meeting for one of the 10 candidates vying for mayor of this 2,000 person town. The woman who invited us had lived in the US for 25 years and was a dual Perú-US citizen. Much to our chagrin, we became the focus of the meeting, which started two hours late, lasted until 11 pm on a weeknight, and ended with bread and hot barley “coffee” being passed around to all present. The participants hold the US in high regard for its democracy, infrastructure and advanced technologies. Their party, Avanza País, more commonly known as the “red train” party, was promoting infrastructure development. They wanted our thoughts about how to attract tourism.

Politics, and the run-up to election day

Since our first day in Perú we have been inundated with campaign advertising for an election that finally took place on October 7. In each tiny town there are many (too many) candidates, each affiliated with one of many different political parties. To deal with rural illiteracy, each party creates a memorable icon that appears on the ballot. Along the rural roads, these icons and the local candidates’ names were painted on the walls of nearly every building we passed, as well as rocks along the highway. The ads sometimes show an “X” through the icon, indicating how the ballot should be marked.

Pickup trucks and vans flying campaign flags drove around blasting campaign songs and messages from speakers on the roof. We arrived at the main plaza of a small town during a well-attended outdoor debate between candidates.

Most Peruvians we talked to complained of corruption and were cynical about the potential for politicians to deliver on their promises. On a small dirt road, a sheep herder asked us if the US politicians “rob” us, like the politicians in Perú do. A chiropractor told us that candidates buy votes from rural people with food or cash, or promises of future cash. A small-town local confirmed that the dozens of townspeople standing around with shovels on the torn-up roads in town were evidence of vote-buying by the incumbent candidate. Locals were apparently given road-building jobs with no training, supervision, or machinery, and virtually nothing was getting done. Despite their cynicism, Peruvians were clearly energized about the election, but it’s also worth noting that voting here is obligatory.

Meanwhile, we just submitted our ballots for the US midterm elections by email!

Stay tuned for our next update on traveling through river gorges and past glaciated peaks. To find out where we are right now, check our Track My Tour page, where we post a photo and blurb every day that we’re on the move. Also, you can get more up-to-the-minute, spontaneous updates if you follow Clark's accounts on Instagram and/or Facebook.